Foreword

As part of my ongoing PhD studies, I recently took a course on teaching literature. We were tasked with giving a mini-lecture to the rest of our classmates in which we pretended to teach a poem to them as if they were undergraduates. I chose to present on Zoe Leonard’s iconic poem “I Want a President” for a few reasons: 1) this was right after the U.S. election and many of my peers here are American, 2) this poem feels widely misunderstood, thanks in no small part to its presentation on the High Line in 2016 which many took as an endorsement of Hilary Clinton, or this Andrea Long Chu interview in which she reads (or in my view, misreads) it as fodder for liberal appeals to electoral power, and 3) since my background prior to English is in art history and visual studies, working with something that was firstly considered a work of art by a visual artist allowed me to connect this piece with my interdisciplinary interests.

I was pleased with how the lecture went and so rather than letting it collect dust on my hard drive, I’m sharing a readable version to start off another year of No Outlet. I hope you enjoy it, and if you haven’t read Leonard’s poem before, please do so first. (Please also note that this is written exactly how I spoke it, and so on a prose level, it doesn’t read like my finest work!)

I think it’s important to begin by explaining that “I Want a President” is not a traditional poem that was published in a book or a literary journal—this typewriter draft that you saw [on the previous slide] is the format in which the poem is circulated as a work of art. Its author, Zoe Leonard, is primarily known for her work in photography and installation, rising to prominence in the early 1990s in New York’s queer art and activist scene.

In particular, Leonard was involved in the well-known group, ACT UP, which stands for the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, and she worked with them to raise awareness about HIV/AIDs and support those with positive diagnoses—something that she references in her poem. The conservative backlash to AIDs in the 80s and 90s and the mountain of loss that Leonard witnessed undergirds much of her work from this period, such as the iconic Strange Fruit, in which she sewed together fruit skins as a gesture of repair, of putting the dead back together. This piece was also an homage to the late artist David Wojnarowicz, whose incredible performance/video work ITSOFOMO and memoir Close to the Knives might be of interest to those who are intrigued by Leonard’s poem. The title also references the 1930s anti-lynching song written by Abel Meeropol and recorded by Billie Holiday; this has been read as an effort to think together the violent dehumanization of minoritized bodies by the American state, spanning and highlighting the intersections between racism, homophobia, and cis-genderism. This turn towards dispossession, of death in plain sight everywhere, seems an apt characterization of American politics and healthcare attributable both to this historical moment and many others.

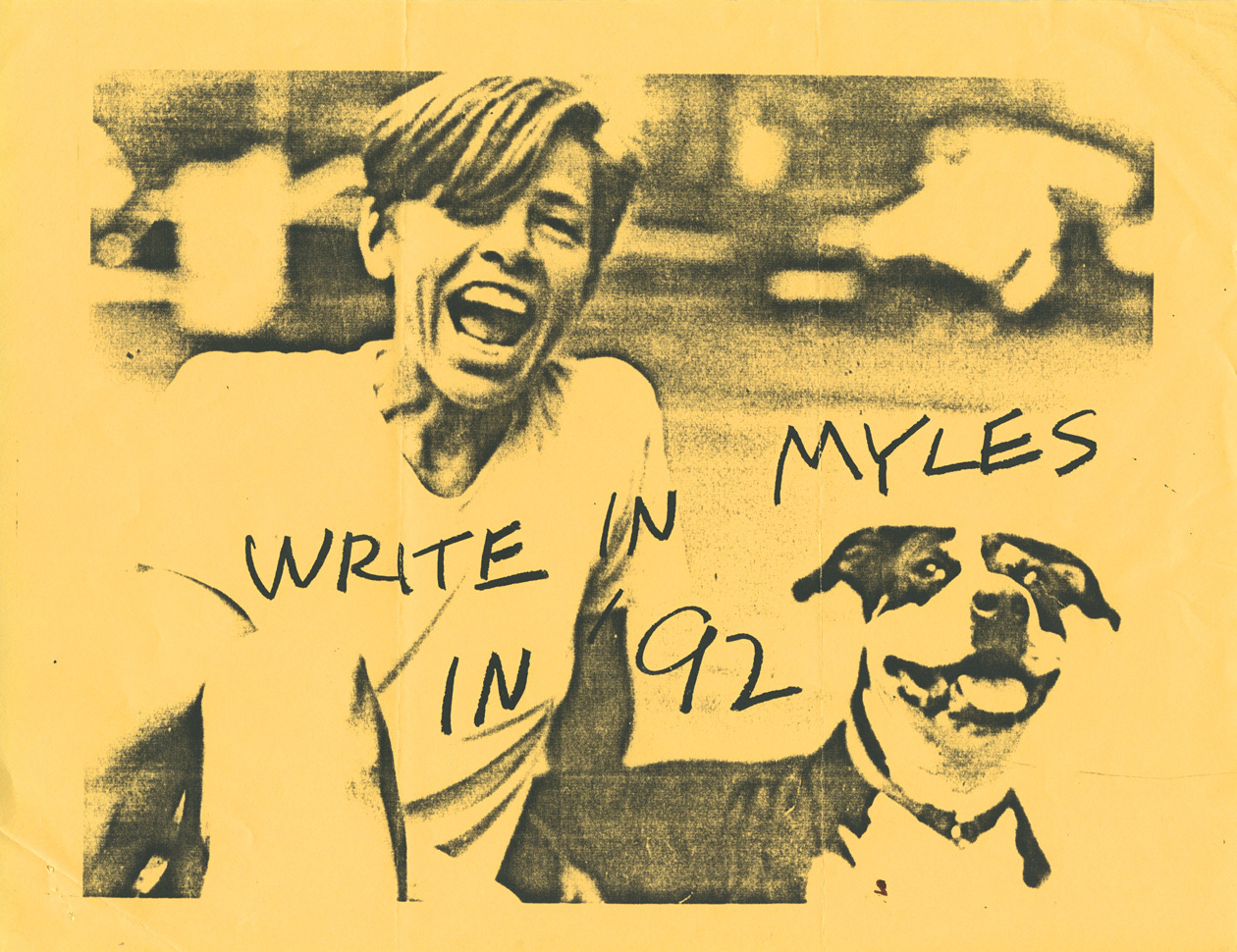

“I Want a President” responds to this frenzy of queer loss, activism, and backlash in the early 90s. In particular, Leonard was inspired by the poet Eileen Myles’ campaign for President as a write-in candidate.

Commenting on their campaign, Myles compares the act of writing in a candidate’s name—as opposed to simply checking one off from a list—to a creative, even poetic act, one which engages the ability to imagine beyond the status quo options that negate queer and trans livability. Consequently, this is a critique of power perhaps more so than a yearning for it.

Oftentimes, Leonard’s poem is read as an identitarian call for equal opportunities to access elected office—as when it was installed on the High Line in New York ahead of the 2016 election. Yet, in other ways it also seems to critique the very notion of elected office itself, or at least the ways in which it is occupied and imagined, both then and now. As I move along, I want you to ask yourself: Does Leonard want power, or is she against it?

Let’s propose that Leonard is picking up on Myles’ notion of a poetic reimagining of voting—of rewriting the rote, often dismaying practice of electoral politics as something more, as something literally for and by the people. I think Leonard’s poem is doing this using three main strategies: firstly, she is disidentifying with the establishment and its power. Second, she is using repetition as a rhetorical and publicity device, and third, she is injecting the image of public office with affect, emotion, and vulnerability.

First, Leonard makes it clear in her selection of ideal traits—someone who is living precariously, who is queer, who is ill, who lacks power over their future—that she is not looking for somebody strong. Instead, she is reworking weakness, proneness, and fallibility into assets rather than deficits. She even crosses out descriptors like “nasty” or “with attitude,” undermining the power of these judging terms that contribute to abjection. Likewise, her web of candidates spans a queer, possibly trans, poor, anti-racist network of solidarity, yoking together these subjects rhetorically by the polysyndeton of ‘and,’ and building this image of coalitional—rather than individual—power in the process. It is as a collective that they are strong, rather than individually, as one might expect through the singular strength of a U.S. President.

Repetition is central to Leonard’s form here: through the anaphoric recourse to “I want, I want,” the engine of the poem is desire. That queer desire was so profoundly pathologized at this moment in time makes the reclamation of wanting—and of wanting something that is not one of the available options—politically charged on multiple planes. And Leonard does not hedge or blunt this desire: to say “I want a dyke for a president” is a demand, it is not phrased as a request.

There is another kind of anaphoric repetition at the end of the poem, with “always a boss and never a worker, always a liar, always a thief, and never caught.” This moment draws on workers’ songs—like union chants—and makes it clear that these issues are not only class-related, but demand a politics of solidarity. Its internal repetition creates a memorable sing-song form, and also enacts the kind of repetitive cycle that it describes.

To that end, repetition is a major part of this poem’s life in that it was largely circulated as a photocopy, a postcard, and a performance: it was designed to be reproduced and shared among grassroots networks, to live beyond the sanctity of the ‘original’ text gatekept by Leonard or a publishing house. Again, the poem becomes a kind of democratic object, something owned in part by everyone!

This social life of poetry—or the interdependency of the poem’s readership—is part of Leonard’s dream for politics. Just as we suggested earlier that she is centering identitarian communities considered irrational, weak, or powerless, she also injects the poem with moments of vulnerability: we get these long, listing lines about heartbreak, grief, and failure. Leonard’s candidate has made mistakes and changed because of them, not shielded themselves from responsibility. We also get a tone of lament in the alliterated sound of “lost his last lover to AIDS” which flows gently, contrasting the sharper sound and diction of other sections of the poem, and reminding us of the need for some kind of softness or human touch that has been evacuated from the sealed-off, macho, plasticized image of the Presidency. The interdependency of life is fragile but beautiful. We might think then of the power she describes as not vertical, but horizontal: both in its interlocking structure, and democratized circulation, but also in its images of proneness.

With that in mind, I leave you again with our inaugural question to answer for yourselves as we depart. Does Leonard want power, or is she against it? Does she really want a President?

Further reading

In 2020, I had the pleasure of interviewing Eileen Myles for Document Journal. We discussed politics, the pandemic, poetry, work, and rescue dogs. You can read our conversation here. I’ve also just picked up their volume Pathetic Literature and look forward to dipping in soon.

[TK images]

What I’m Reading:

Modern Poetry by Diane Seuss: my favourite poetry collection in an age! Seuss’ imagery, the world she conjures, her love of poetry’s history… it’s all just folded together so perfectly (gentle, but crisp). I can’t recommend this enough.

August Blue by Deborah Levy: I haven’t had time to read many novels recently—this one felt like a low-stakes re-entry. The first two thirds feel driven by images and ‘vibes’ in a way that I loved; the final move towards closure was unsatisfying for me, though.

Enemy Feminisms by Sophie Lewis: more to come on this one!

What I’m Watching:

Rewatching Community for some comfort while dealing with the puppy blues