Charlotte Wells' 'Aftersun'

An excerpt from my live reading at "Bring Me the Head of" last week

Foreword

Last week, I was honoured to be included in a lineup of 8 Toronto-based film critics who read work at Saffron Maeve’s event “Bring Me The Head of…” at the Tranzac Club. Saffron was inspired to consider the potentials of live reading after being asked incessantly at panels and Q&As whether film criticism “counts” as art. In gathering and giving voice to our work, we all brought attention to the rhythms and pleasures of language and to the idiosyncracies of voice that each individual brings to their critical practice.

For my reading, I put together a pile of thoughts that I am working out about Charlotte Wells’ 2022 film Aftersun, which I think is one of the best directorial debuts I have seen in years. I am working towards turning this into a conference paper over the winter, hopefully to be followed by an academic article. In the meantime, I’ve used the occasion of the live reading as an opportunity to loosely sketch out some of my main concerns and how they connect to one another. It was also an opportunity to approach an academic project in a different way: not from the isolated place of writing and thinking by myself, roped in by conventional style and structure, but instead, to think about audience reception, lively prose, and communal response. I loved hearing from attendees about how this interpretation chimed with theirs and all of the beautiful ways in which this film has lingered with those who love it. In that spirit, I’m sharing this work in progress or early map of my thoughts and look forward to discussing it with even more of you. <3

The philosopher Giorgio Agamben once said that the element of cinema is gesture, not image.1 He wrote of cinema’s emergence in the late-19th century as an effort to recapture and preserve the gestures of the bourgeoisie: in other words, cinema as a record of the body, especially the bodies that we cannot save and take with us, the bodies we have lost, or are losing.

In Charlotte Wells’ 2022 debut feature Aftersun, a gesturing and flailing body jostles around the opening frame, its torso twisting and dancing, immortalized on 1990s VHS. “What even is that?” asks 11 year old Sophie from behind the camera. “These are my moves!” exclaims Callum, her father, as he turns away, still swaying. The pair are on vacation together, an annual tradition since Callum split with Sophie’s mother. Wells’ film toggles between scenes of their Turkish holiday, moments recorded on their camcorder, and scenes of Sophie in the present, as she recollects their time together, which we eventually come to realize may have been one of their last.

At the end of the film, we discover that the VHS inserts are being replayed by this present-day Sophie, arranged with a retrospective glance, such that on later viewings of Aftersun, it is hard not to think that the younger Sophie is already making these recordings for her older self. Whether she knows her father will die is indecipherable, although Calum himself tells a stranger, “I can’t imagine myself at 40. I’m surprised I even made it to 30.” Later in the scene, he goes scuba diving after lying about having a license, a story Sophie recounts to the camcorder in anticipation of his resurfacing. She points the lens at the ocean, undisturbed, a vacuous absence. She waits.

At the heart of the impulse to record is almost always the anxiety of loss. What we are left with however is an imprint of the thing, never the thing itself, and so the image always exists in the tension between that which is preserved, and that which disappears.

Wells’ film is, for me, about this very ontological condition of cinema—it is a portrait of the artist as a young woman and how her sensibility for noticing and remembering is forged in mourning. In one scene, Calum asks her to stop recording and takes away the camcorder, to which she says, “ok, I’ll just record it in my little mind camera.” Memory and the camera have become one. Later, Sophie and Calum hug before bed and she looks at their reflection in the sliding glass door—the memory is already, has always been perhaps, an image. She is learning to literally organise the present into frames, so that it can become the past.

But what of gesture and the body? The study of gesture is covered under the umbrella of performance studies, whose leading practitioners have adamantly argued that, in the words of Peggy Phelan, “performance’s only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance… Performance’s being …. becomes itself through disappearance.”2 As paradoxical as it sounds then, gesture is made up of loss, it rises and falls, hangs and drifts away. Calum’s moves can be recorded, but this is no substitute for the complex interaction of liveness. Sophie films him dancing or doing Tai Chi; he records her waving goodbye, over and over again, at the airport. Their exchange of the camera, their attempts to preserve the thing about the Other that is always ephemeral, is a kind of language of love—an attempt to say “I want to keep you with me. I want this to go on.” Yet it is also an acknowledgement that it cannot.

In her book on the queer life of gesture, Juana María Rodríguez writes that “gestures emphasize the mobile spaces of interpretation between actions and meaning…. [they] are where the literal and the figurative copulate.”3 The sweep of an arm or the scratch of a nose feel like a container for another person because of their idiosyncrasy, not because it is transparent what these movements represent. When Sophie—or Sophie’s camera—watches Calum dance one night while smoking on the balcony, he dips in and out of motion, rocks from side to side and cuts the air with a hand, then stops and hangs his head, then sways again. The world of the balcony is partitioned from the hotel room, where Sophie’s breathing dominates the soundtrack, and so the night beyond—where he is—is completely sealed. They are briefly in disjointed worlds: where is he going and why is he dancing? What is motivating “his moves”? The other’s body has its own life, not only one that confusingly both solicits and evades documentation, but one that is stubbornly ambiguous, unknowable.

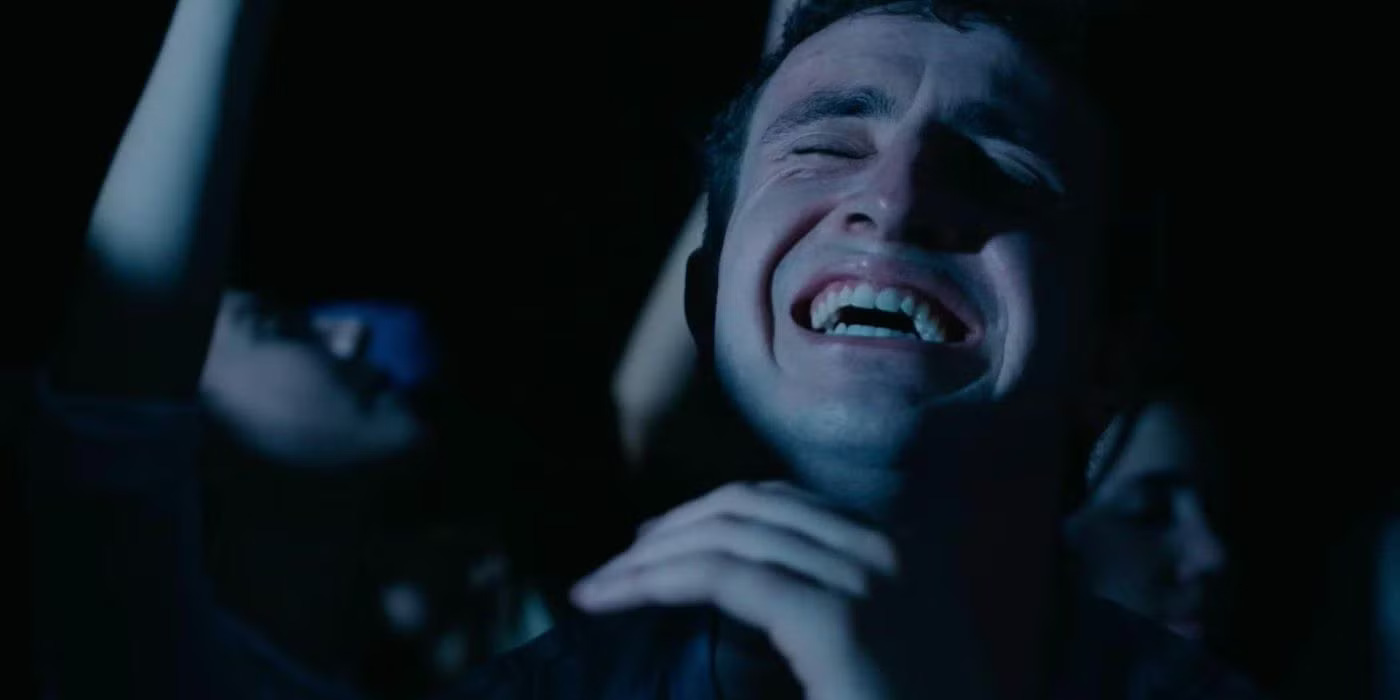

Sophie also sees Calum dancing at a rave. Or does she? The film offers us a number of brief interludes in which grown up Sophie navigates a dark room of partygoers under strobe lights. In flashes of illumination, we see her glimpse him from far away, then sometimes up close, as he thrashes and sweats. Everything is under the fog of darkness, motion, and imagination, but it seems that he is dancing with men, a fact often cited in the many queer readings of the film that populate Reddit. We know that Sophie, like Wells, is queer, and that these sequences, being figurative or imagined, might suggest that she is asking whether her father was too. Redditors spy his reaching for another man’s lapel on the dancefloor here, or in the A-plot, his prolonged eye contact with a scuba instructor. In any case, there is something fitting about the film’s relationship to not knowing, not being able to grasp anything firmly in both hands, and the floatiness of queer evidence, which Jose Muñoz reminds us has existed not as clear proof but “as innuendo, gossip, fleeting moments, and performances that are meant to be interacted with by those within its epistemological sphere—while evaporating at the touch of those who would eliminate queer possibility.”4 Muñoz cites gesture as ephemeral queer evidence, and as a sensual aesthetic strategy for ecstasy, a flight path to another here and now where being is possible. If queer loss points to the inhospitality of the status quo, does the film invite us to imagine spaces outside of time and space to which someone might escape?

If so, this is a place with which Calum gets in touch through dancing, affirmed both by his spontaneous outbreaks of motion throughout the film, and the penultimate, devastating scene of Sophie and Calum’s last dance. On the final night of vacation, father and daughter have dessert and walk around the hotel. Calum, again embarrassing Sophie with his “moves,” joins a group dancing to “Under Pressure,” the anthem by queer icons Queen and David Bowie. As Sophie finally joins him, Wells employs parallel editing to synthesize this moment with the rave in her imagination: in Turkey, they jump, sway, and hug, Sophie gripping him tightly in anticipation of their coming split, when she will fly back to her mum. In the rave, they argue, they push each other, they hold each other, they fall onto each other; in flashes of their dance, we see flexed hands and fingers digging into backs, a kind of bodily scrimmage for recognition, choreographed like the dramatic tableauxs of a Caravaggio painting. And then Sophie lets go of Calum, watching him fall into darkness. The strobe light obscures most of what is happening, but for a moment, the elder Sophie is gone, and her 11 year old self stands in her place smiling as her father recedes. The density of the rave’s darkness, so infrequently punctured by light, lends to the confusion of what happens to Calum, but also of the inevitable afterlives of loss in guilt, disorientation, and the inability to repair and return to the lost body. The song crescendos, with Bowie belting:

'Cause love's such an old-fashioned word

And love dares you to care for

The people on the edge of the night

And love dares you to change our way of

Caring about ourselves

This is our last dance

This is our last dance

In her little mind camera, Sophie is still dancing and fighting with, still holding onto, still trying to preserve her father. He is in motion, a moving target, leaving traces, some that make the frame and some that the camera cannot penetrate.

When Wells was 11, she also went on a holiday with her father to Turkey, and in Aftersun, Sophie and Calum recreate a photo taken of the two of them at the hotel restaurant. Wells’ father died when she was 16—a loss that is the subject of her previous short, Tuesday. Like Sophie, her career as a filmmaker has explored the use of cinema as a tool for picking loss up and turning it over, examining its sides as the lost object slips through your fingers. Freud might say then that cinema is melancholic: it remains attached to something that is gone, it disavows the loss. If so, I think that Wells has managed to make her film at the nexus of the desire to keep and the knowledge that you can’t, of lovingly capturing gestures and dance moves that are swift and momentary, that can never be repeated or experienced the same way twice, that must be savoured but cannot be seized. This may be our last dance, but we will try to go back, again and again, through the glow of the screen, and through the moves we have shared.

Currently:

What I’m Reading:

My friend Hannah’s new Substack, Fan Mail

Radical Virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and the Black Atlantic by Genevieve Hyacinth

How We Write Now by Jennifer C. Nash

The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

What I’m Watching:

Detroiters, a TV show from the late-2010s that stars Tim Robinson (of I Think You Should Leave) and Sam Richardson (Richard Splett from Veep) as adult best friends who run a local ad agency. Both are incompetent but incredibly earnest about their jobs. The show is super silly—feels somewhere between where ITYSL ends up but with shades of Portlandia and maybe New Girl?

The OZ reboot of The Office, which I controversially like.

What I’m Writing:

My first dissertation chapter, on witnessing/performing sexual violence, ethics, stillness, and the ambiguity of others in the work of Alice Munro and Ana Mendieta.

Thank you for reading No Outlet! If you liked this, you might enjoy some of my previous writing on films below. You can also see my academic criticism and public criticism on my website at tiasdiary.com.

Agamben, Giorgio. “Notes on Gesture” in Means Without End: Notes on Politics. U of Minnesota Press, 2000.

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. Routledge, 1993.

Rodríguez, Juana María. Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and Other Latina Longings. NYU Press, 2014.

Muñoz, José Esteban. “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts.” Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory 8:2 (1996).