Fall/winter cinema diary

Top notes are: weird and wandering. Waiting, holding onto a secret, a mysterious stranger haunting or protecting somebody. These are the things best done in the dark of winter.

All We Imagine as Light, dir. Payal Kapadia (2024)

I caught this year’s Cannes Grand Prix winner during its opening weekend in Toronto and I was struck in particular by its use of colour and rhythm. Almost all of the film is shot at night, emphasizing the moments when nurses Prabha and Anu are changing shifts, catching the train home, escaping for a rendezvous with a forbidden lover, or throwing rocks at a new development advertised “for the privileged.” The pink/blue palette offers visual tones that are deep and soft. For the score, Kapadia draws together a piano theme by the Ethiopian nun-turned-composer Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou along with 80s synth sounds. All of these decisions, I think, foreground ecclectic idiosyncracies and personal pleasures, rather than delivering the kind of homogenizing nationalist cinema that a festival like Cannes might normally solicit.

When I Saw You, dir. Annemarie Jacir (2012)

A friend and I hurried to this screening last-minute during TIFF’s retrospective From Palestine with Love: The Films of Annemarie Jacir, and we were so glad that we did. As the lights came up, we both turned to one another in tears and immediately declared it among the greatest films we had ever seen. Jacir—who was present at the screening, visiting from Palestine where she is working on her next project—sets this narrative of refugee life during the 1967 conflict known as the “Six-Day War,” focusing on a young boy who does not understand why his mother will not take him home and why they must stay in a Jordanian camp instead. Without a satisfactory answer, he one day decides to walk back to Palestine, encountering a group of freedom fighters who take him under their wing. What begins as a childlike naivety in fact becomes a rallying cry, a stubborn insistence that rings true: why can’t he go home? Why should he accept exhile? Why should he be made to wait? His innocence is in fact a knowingness, a refusal of the status quo both then and now.

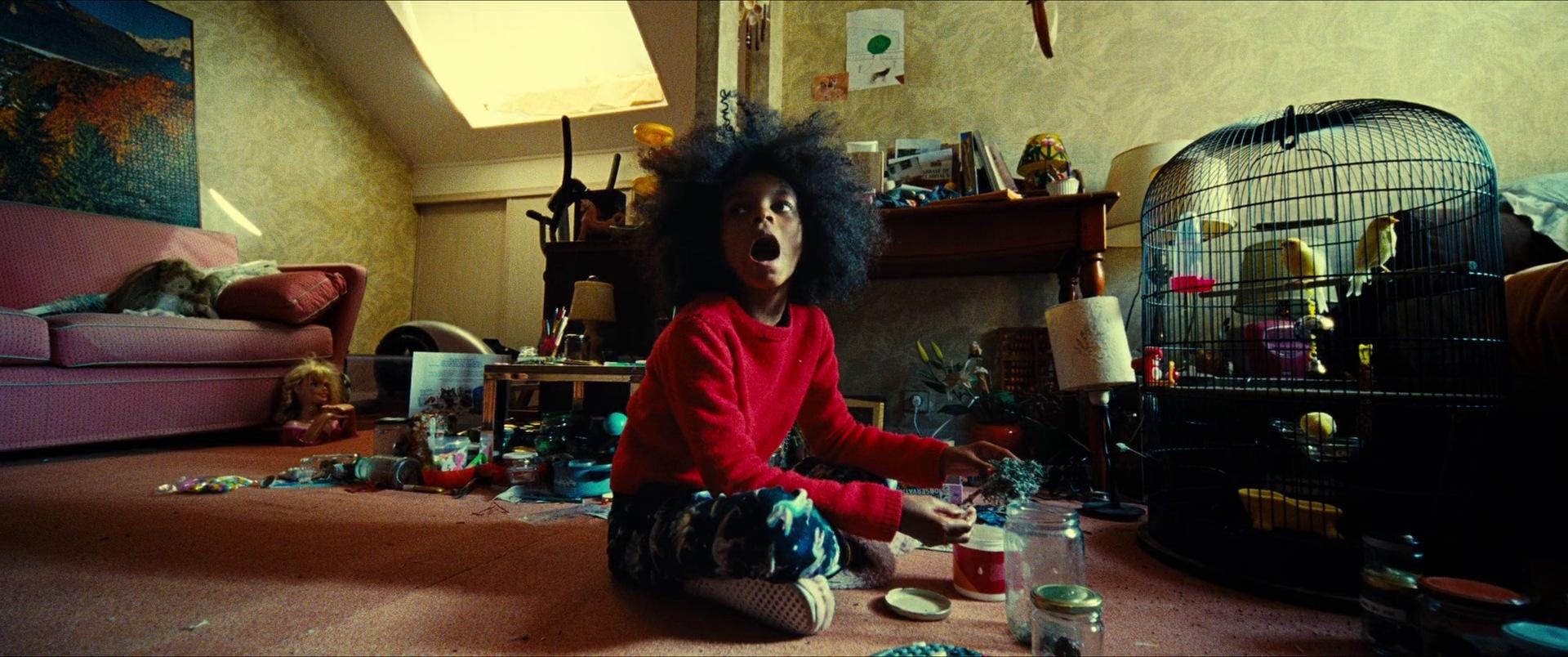

Bird, dir. Andrea Arnold (2024)

Bird is dropping on Mubi this month, but I saw its North American premiere at TIFF in early September. I have long been a fan of Andrea Arnold’s, having written multiple papers on both American Honey and Fish Tank. For me, Bird takes the premise of these two films in particular and dials them up to 100—the camera is almost always in motion, jostling between exhiliration and terror and soundtracked with the bass alllll the way up (though Arnold’s films always address the intersection between poverty and violence, this one is perhaps her most graphic depiction of domestic/familial abuse). I’m also reading Bird as a film about gender nonconformity: its protagonist Bailey longs to be one of the boys, but instead finds a guardian angel figure in Bird, the androgynous stranger who appears out of nowhere one morning and watches over Bailey from atop buildings. Both are in search of acceptance from their family, and instead perhaps find it in one another—but also in art, nature, and strokes of the surreal that are new to Arnold’s historically realist repertoire.

The Five Devils, dir. Léa Mysius (2022)

In Mysius’ sophomore feature, a young girl named Vicky is driven to reproduce and collect the scents of those she loves—namely, her mother, to whom she is deeply attached. When her mother’s ex is released from prison, Vicky’s scents also take on the power to unlock memories, and she becomes a witness to the complex intimacies and crises that led to making her mother’s life what it is. This is a wholly singular film and one of the only ones I have seen that privileges a non-visual sense like smell, demonstrating its power as a channel between the past and present.

To Sleep With Anger, dir. Charles Burnett (1990)

Though Burnett is mostly known as a leading figure of the LA Rebellion—a cinematic movement in the 60s and 70s led by African-American filmmakers out of the UCLA film school—films like this one offer a more oblique approach to political cinema, relying on intimacy, humour, and the daily representation of community to do its work. In fact, although To Sleep With Anger is marketed as a thriller, its pacing is not oriented toward action, and suspense unfolds only at a low level, as a kind of ambiguity or foreboding at best, soliciting an intuition that something isn’t quite right with Harry (a sudden guest from the past, played by Danny Glover). I saw a screening of the film presented by Dionne Brand and Christina Sharpe, and in the Q&A, they spoke about the humour of being in proximity to people who do things that are strange, and who feel license to do such things because of an intimacy that is at once sliced into by the interruptions of strangeness. In that sense, Burnett perhaps captures the strangeness of becoming familiar.

Dick, dir. Andrew Fleming (1999)

This film is not new for me—friends will know that I have already seen it at least four times this year—but when the Revue held a 25th anniversary screening on November 5, I at last had the opportunity to see it in a theater! Dick is a perfect movie to me: it’s a bubbly, smart 90s comedy in which two teen girls (played by Michelle Williams and Kirsten Dunst) accidentally become the whistleblowers who uncover Watergate, end the American invasion of Vietnam, and bring down the Nixon presidency. It combines all of my favourite things: 70s fashion, girls getting up to shenanigans, political satire, ABBA, journalism, and fighting the U.S. war machine. Where are Betsy and Arlene now?!

Measures for a Funeral, dir. Sofia Bohdanowicz

Another TIFF title for me! Bohdanowicz’s exploration of grief and the reanimation of history is ambitious and roving, even if it didn’t always work 100% of the time. In it, a PhD student called Audrey looks for traces of the overlooked Canadian violinist Kathleen Parlow, chasing her ghost from Toronto to the British countryside and Nordic symphony halls. As Audrey arranges the restaging of Parlow’s concerto, her mother—also a musician whose career was stifled because of her gender—is dying. Though I often found the dialogue to be wooden, Measures offers intense and specific visions of regret and denial. What’s more is that in real life, Parlow was the violin instructor to Bohdanowicz’s own grandfather, and so the film endeavours to repair very real gaps in the history of Canadian music.

Queer, dir. Luca Guadanigno (2024)

I’ll be writing more about this in a forthcoming freelance assignment, but in the meantime I’ll be brief: this is definitely Guadanigno’s big-boy movie, a real step away from the commercial, straightforwardly narrative orientation of hits like Call Me By Your Name or Challengers. Instead, Queer is unafraid to be a difficult text, seducing you with its lush visuals and literary dialogue, and then intervening with long surreal passages that I’m not yet sure how to make sense of. I think it’s a good film—not mind-blowing, but well-executed. I wonder how others will feel about its interpretation of the source text, William S. Burrough’s novel of the same name; the filmmakers imagine this as a love story, whereas I originally read Allerton (Outer Banks’ Drew Starkey) as ultimately ambivalent and Lee (Daniel Craig) as obsessed, using this ‘love’ as a transitional object (or substitute addiction) while he detoxes from heroin and the murder of his wife. Excellent needle drops throughout, especially of Sinead O’Connor and Fleetwood Mac…

Fertile Memory, dir. Michel Khleifi (1981)

When the tutorials I was leading read excerpts from Edward Said’s After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives this semester, we also had the opportunity to screen this documentary, since it is one of Said’s main intertexts. In particular, the film draws attention to the everyday labours of Palestinian women as they sustain their families, transmit intergenerational memory, and navigate dominant ideas of what it means to mobilize for their people. The film is slow and observational, paying homage to what makes up the everyday, and also seemingly influenced by traditions in European feminist cinema (there were shades of Chantal Akerman, I thought).

The Age of Innocence, dir. Martin Scorsese (1993)

Since reading Summer in an MA class a few years ago, I’ve been enthusiastic about gobbling up more Edith Wharton. Oddly, I’ve not yet made it to The Age of Innocence—her Pulitzer-winning classic—but I did enjoy Scorsese’s oppulent adaptation, particularly the care he takes to lavish on Wharton’s obsessions with architecture and space (something that cuts through much of her writing and life—she designed her own home, The Mount, in the Berkshires). I was also deeply impressed by Michelle Pfeiffer’s performance as the ‘other woman,’ and the ways in which she makes even old-fashioned text sound completely natural and spontaneous. She joins Winona Ryder in schooling Daniel Day-Lewis’ Archer, who always presupposes his own control over everything—spoiler alert: he is the titular innocent, whiny baby!

Thank you for reading No Outlet! If you liked this, you might enjoy some of my previous writing on films below. You can also see my academic criticism and public criticism on my website at tiasdiary.com.