For those joining me now, I am in the third and final week of my PhD Special Fields exam, the qualifying stage that allows me to go forth and write my dissertation, having (hopefully) proven my mastery of my primary fields.1 As I have been in this process, some family and friends have assumed that it will mark the end of my PhD, when it is in fact more of an inaugural stage! PhDs in my field tend to take at least 5-6 years and I am only finishing the 2nd, so there are yet miles to go before I sleep. This tends to surprise and confuse people, and in general, I would say that talking about my degree to non-academics makes me feel a bit like an alien—why does it take so long, why is this worth doing, what on earth do I study… all of these questions seem to have opaque, vacillating, and abstract answers. Maybe I’m wrong, but I imagine this is acutely frustrating for folks in the humanities, who are less easily able to describe a concrete outcome to our work than those who can point to a policy, product, or invention. We are instead intervening in ***knowledge*** or in ‘how people think’…consequently, explaining my work can feel on the one hand like I’m pontificating on high, while on the other hand, trying to break things down accessibly can be its own kind of condescension. I often don’t know how to talk publicly about what I do in a way that feels right to anybody, including myself!

Here’s what I say to other academics in my field: my research investigates bodily comportment in feminist literary & cultural production, particularly the social, philosophical, and interpretive demands of gesture and posture. My specialization is in American literature of the 20th- and 21st-centuries, and my dissertation will look specifically at the 70s and 80s. My areas of intellectual commitment include gender/sexuality studies, feminist theory, critical race theory, performance theory, and aesthetics & ethics. But what does this all actually look like?

In undergrad, I started thinking about the gendered ways in which bodies are conditioned to move, somewhere between reading Judith Butler’s “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution” and taking a course called “Fashion, Culture, and the Body” at NYU London. I had been a dancer from the age of 10 and then started working in fashion at 15, and so I came of age very much surrounded by particular (and often inflexible) choreographies of femininity, many of which did not feel totally comfortable to me. In real life too, I started to feel as though I need blocking, or someone to set out where and how I was meant to stand. I was always hyper-conscious of my body and had the sense that I was doing something weird with it, and so I found solace in two things: feminist phenomenology, particularly Iris Marion Young’s essay “Throwing Like a Girl,” in which Young breaks down the ways in which girls are taught not to use the full lateral potentials of their bodies, as well as feminist art by people like Ana Mendieta, Francesca Woodman, and Carrie Mae Weems, who conscripted gesture and pose to show the gendered body in a different light, or in various poses of resistance, abjection, care, and collectivity. I imported these interests to my graduate work in Cinema Studies, and eventually, to English.

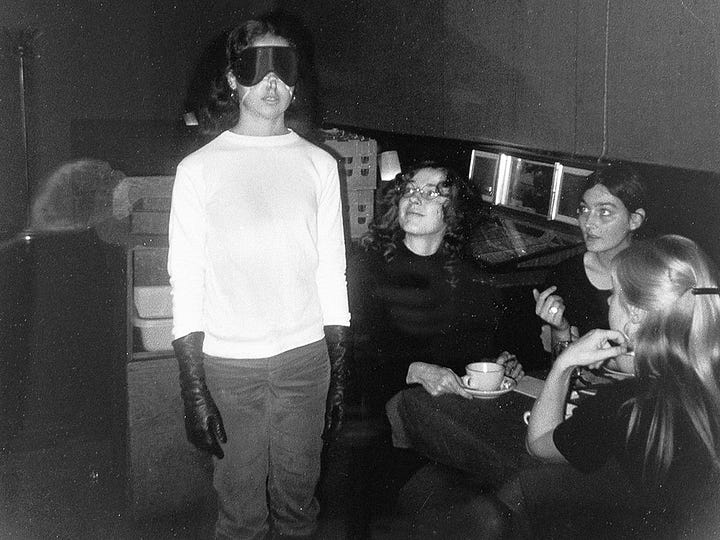

Here is another way of introducing the ideas: in her April 1970 performance Untitled for Max’s Kansas City, the artist Adrian Piper arrived at the iconic artists’ bar wearing gloves, ear plugs, and a blindfold. Her intention was to navigate the bar in a totally insular, individualistic manner, with no concern for her surroundings—in other words, to mimic the embodiment of certain kinds of white masculinity. I find Piper’s performance here exemplary for two main reasons: first, the ways in which it points to how bodily comportment mediates (and is mediated by) how we relate to others and to the world, and second, for the ways in which bodies can be misrecognised, since the audience moved out of her way and watched, and thus Piper’s performance did not land in the way she had intended. Bodily comportment, then, cannot be pinned down as a purely intentional and transparently received act—it shows us the ways in which we relate to and live with one another through the fog of interpersonal opacity, dependent on each others’ reactions, reception, and mis/understanding.

My efforts here are to think about how we “read” bodies in literary studies, and how this might need to change. Though this is in a lot of ways an oversimplification, we can still say that literature is traditionally taught as an object to be decoded, where specific and intentional meaning can be unearthed and brought to light. But to treat bodies and behaviours in the same way can lead to the kinds of violent taxonomies and positions of mastery that, for instance, circumscribe what gendered bodies can be or look like, or that have historically produced ideas of racial difference and hierarchy. The idea that a body’s outside tells us something essential or immutable about the subject in question is almost always incorrect, violent, and assumes a kind of penetrative insight that shores up the authority of the one who sees/describes. As a result, I turn away from reading literary bodies through the frame of literary decoding, and pivot toward the affordances of a younger field, called performance studies.

Performance studies tends to focus on anything from the theatre, to traditions and rituals, to what Diana Taylor calls “the aesthetics of everyday life.”2 Though there are many competing definitions of what performance is, my provisional definition right now is: an arrangement of the body that is, in some way, witnessed.3 This field offers a method that thinks very deeply about what it means to witness, in addition to thinking through how bodies are arranged/arrange themselves in ways that are politically, culturally, and socially salient. It is more interested in these kinds of relationships—between body and culture, body and audience, body and subject—than in ascribing to the body a particular, fixed meaning (i.e. not X gesture means Y feeling, but X gesture interfaces with ABC aspects of the environment, politics, or culture, and enables FG ideas to emerge). This is one of many reasons why I find this field very generative.

So, back to the dissertation. I am proposing a reading of American feminist literature and performance (including films, photography, and video art) from the 1970s and 80s that uses a performance studies method. This will allow me to consider how bodily comportment articulates alternative ways for bodies to relate, or what a lot of theorists in queer theory and Black studies refer to as the emergence of alternative “socialities.” For instance, I like this quotation from Juana María Rodriguez, who writes that gestures “form connections between different parts of our bodies; they cite other[s’] gestures; they extend the reach of the self into the space between us; they bring into being the possibility of a ‘we.’”4 Likewise, Rebecca Schneider thinks about how gestures are responsive: they solicit a witness who is called to somehow engage, synthesize, and reciprocate.5 I am also thinking about posture, which has a similarly relational underpinning: in the history of philosophy, the idea of the human (and of freedom, rationality, ethics, etc.) is organised around the vision of an upright man who is not bogged down by dependence on others, who can self-regulate and self-manage. This figure is obviously a fiction, since life is interdependent and there is no one who does not at some time or another need support; consequently, feminist theorists like Adriana Cavarero, Kemi Adeyemi, and Sarah Jane Cervenak have posited inclination or the leaning, wayward, bent, prostrate, tilting body as alternative poses for living, caring, desiring, etc. What if we imagined humanity from this angle instead, especially as it has been occupied largely by non-white, non-male, disabled, queer, working, and otherwise-marked-as-irrational subjects?

Consequently, my project is provisionally titled Posing Alternatives: Bodily Comportment and the Feminist Imagination, and in it, I will ask questions like: what alternative poses might we take, and what alternatives might be posed by feminisms, broadly conceived?

Part I thinks through the ethics of reading bodily comportment. My first chapter reads sexual assault in Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women (1970) which is depicted in the novel as a kind of performance. I think about the ways that bodies communicate unevenly, and how this ambiguity is exploited by Del’s assailant, but also how feminist performance artists in the 70s staged sexual assault in their work to draw attention to the slipperiness of witnessing, knowing, and interpreting violence. The next chapter thinks about the ways in which Black feminist performers and artists speak back to a history of being made to appear as evidence or prove themselves, and so strategically deploy gesture as something that is expressive but ultimately exceeds understanding—artists like Lorna Simpson, for instance, turn away the surveying gaze of the camera with its historical connotations of documentary and use the body to deliberately confound readability. This chapter draws on thinkers like Hortense Spillers, Kevin Quashie, Tina Campt, C. Riley Snorton, and Nicole Fleetwood for thinking about how gender is de- or re-territorialised.

Part II thinks through what bodily comportment is actually doing in literary texts—how are new relationships, politics, ethics, and social forms emerging from the ways in which bodies move and arrange themselves together? Chapter 3 will read Marilynne Robinson’s novel Housekeeping, where I look at household labour as a set of repetitive gestures that constantly repeat but fail to create anything that remains—food is eaten, the house collapses, the rowboat stays stuck in the same place. Whereas Marxist feminists have theorised the home as a site of social reproduction (what Simone de Beauvoir might also have described as the consolidation of “bourgeois values: faithfulness to the past, patience, economy, caution, love of family, of native soil”), the bodies in Housekeeping fail to reproduce social norms, a failure articulated by their fruitless gestures. This, I will argue, enables a queer reading of the novel, where Ruth and Aunt Sylvie discontinue generationally transmitted normativity and do not ‘reproduce’ the nuclear family but pursue other kinds of kinship. And yes, don’t worry art historians, I am reading it with Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), a famous work of video art in which the artist mimes the alphabet with kitchen implements, moving in exaggerated and strange ways to defamiliarize the image of the kitchen as the unchanging, happy centre of the domestic sphere.

Finally, chapter 4 will read posture in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. This novel is so rich, layered, and astounding that I don’t have a coherent thesis under which to yet gather my thoughts, but I am investigating how leaning is both a sign of living under violent conditions for enslaved persons, while also being a site at which Sethe and others exchange care and desire. Uprightness is a violent disciplinary standard, one that is in fact propped up by the leaning bodies of others. This trajectory does not take the idealised, vertical figure of rationalist man as its ambition, but locates other kinds of freedoms, relation, and ethics that happen in the midst of constraint and that foreground collectivity, or the need for others (including the vacillating exploitation and prohibition of this need, where mothers were separated from their children, for instance). I’ll think about this alongside Spillers again and Alexander G. Weheliye. I don’t think I will have a visual text here, since there is always so much to say about Morrison, and never enough time or space to say it.

In essence, I started thinking about bodily comportment some 6-8 years ago in undergrad, then concerned mostly with its relationship to gender expression, but eventually turning to more ethical matters, or questions about how bodies transform the conditions of the world (or how we can transform the conditions for bodies, as in how and what we read for in them). As any senior PhD student will tell you, I know that my project will still change significantly and that perhaps some (or all) of these chapters will become something else. But since academia is so mystifying, and the humanities in particular are right now very misunderstood, I wanted to try and practice making this little bridge, or point of sharing (and hopefully exchanging) thoughts. I am just a girl who loves ideas and has the privilege of getting to work with them as a job, at least for now, so I thank you for indulging me—I hope this was in some way interesting, or at least clarifying!

What I’m reading:

Isabella Hammad’s Enter Ghost (currently)

Miranda July’s All Fours (finished, coverage to come)

Sofia Coppola’s ARCHIVE (on the couch, with a cup of tea, in the evening)

Next in queue (unordered): Lauren Groff’s The Vaster Wilds, Sina Queyras’ Lemon Hound, Claire Louise Bennett’s Checkout-19, Sunetra Gupta’s The Glassblower’s Breath, Jacqueline Harpman’s I Who Have Never Known Men, Catherine Lacey’s Biography of X, Freud’s Civilization and its Discontents, Amber Jamilla Musser’s Beyond Shadows and Noise

What I’m writing:

Prepping an interview that will come out next week with a filmmaker whom I adore

Soon to start prepping two new book reviews, one of which may appear in the newsletter and one of which is for an arts magazine

What I’m watching:

Todd Haynes’ Safe (1995)

Luca Guadanigno’s Challengers (2024)

Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967)

Cecilia Vicuña’s What is Poetry to You? (1980)

Anonymous, Flowers and Grenades (1968)

Ironic that the term “mastery” is the one the department uses, when so much of what I have written about in my exam so far is my project’s aversion to mastery, both politically and intellectually.

This is from The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas, though I would also suggest her volume Performance as an excellent view of the discipline for beginners and beyond.

This witnessing can happen in any number of ways—witnessing of the self or by others, live, or in documentation. I am less of a stickler for liveness, for instance, than some theorists like Peggy Phelan or even Taylor tend to be.

Sexual Futures, Queer Gestures, and Other Latina Longings.

“That the Past May Yet Have Another Future: Gesture in the Times of Hands Up.”

Your mind! Thank you for sharing and for teaching me so much!